The ‘A’ status for the Indian NHRC has been deferred three times, for non-compliance with some of the Paris Principles for human rights bodies.

NHRC

Published on: 12 Mar 2025, 6:22 pm

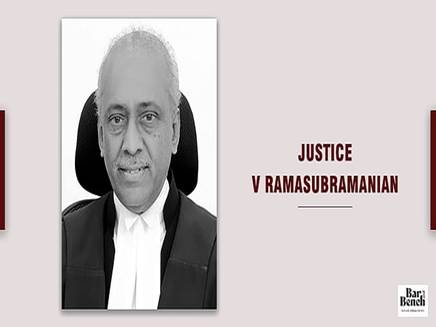

After the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) remained headless and memberless for months, former Supreme Court judge Justice V Ramasubramanian was appointed as its new Chairperson. Two new members have been appointed along with him.

The Protection of Human Rights Act of 1993 (PHRA) mandates the presence and consent of the leader of the opposition party in both houses for appointment of the NHRC Chairperson. The recent appointment process sparked much debate, as the leader of opposition in both houses strongly opposed the appointment of Justice Ramasubramanian.

Leaving all this behind, there are several repairs that need to be done to bring life back into the NHRC. Transparency, diversity in appointments and independent functioning are the major concerns. But first, we look at the legacy of the new Chairperson to understand his ability to revamp the Commission.

Justice Ramasubramanian’s contribution to human rights as a judge

Justice Ramasubramanian has made an immense contribution to the field of human rights, especially in adopting a victim-centric approach through a variety of judgments. As a Madras High Court judge, he issued a proactive order in B Dilipkumar v. Secretary, directing the State to create special cells and dedicated helplines in every district to tackle the menace of honour killings in Tamil Nadu.

In Anand v. Vanitha, he ruled that in cases where the custody of the child is disputed, it is the rights and the interest of the child that should be given primacy over what the parents claim. In Aparna v. Ajinkya, he defended the privacy of a child by not letting the child undergo DNA profiling to prove the allegation of adultery against his wife. In this particular case, it was also held that the DNA profiling orders for children in similar cases should never be passed mechanically.

V Ramasubramanian

In State v. Rasu, Justice Ramasubramanian dismissed an order laid down by a single bench of the Madras High Court directing devotees to follow a ‘dress code’ while visiting temples and held that the dress code for the devotees is beyond the scope of the lis and therefore cannot be approved.

As part of a Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court in the Kaushal Kishore case, he delved into the longstanding debate on the horizontality of fundamental rights. The Court held that Article 19 (right to freedom of speech) and Article 21 (right to life and personal liberty) of the Constitution of India are enforceable against persons other than the State or its instrumentalities.

Core issues faced by NHRC

Although Justice Ramasubramanian has a proven record in protecting human rights, any person who enters Manav Adhikar Bhavan (which houses NHRC in Delhi) is bound to face difficulties.

All national-level human rights institutions must meet the minimum standards set by the Paris Principles laid down by the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) in 1993. It was in fact in furtherance of these principles that the NHRC in India was formed. Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions (GANHRI), a UN-linked body, brings together human rights institutions at the national level and monitors their compliance with the Paris Principles. The sub-committee on accreditation (SCA) of GANHRI gives grades to the NHRIs (A and B status) based on their compliance with the Paris Principles. The ‘A’ status for the Indian NHRC was deferred three times – in 2011, 2016 and recently in 2024 – for non-compliance with some of the core principles, including autonomy from the government, pluralism, and independence in the appointment process.

What do the Paris Principles say?

The Paris Principles, 1993, in its simplest form, sets out the bare minimums of human rights bodies to function efficiently without interference from the executive. The SCA’s primary concern while it deferred ‘A’ status for India in 2024 is the transparency and independence in how it appointed the Commission members and the Chairperson. The SCA also recommended filling the vacancies, adopting a more transparent and independent appointment process, allotting dedicated police officers to take up the NHRC’s investigations, and, most importantly, ensuring pluralism in the Commission by including all ethnic minorities, socially backward groups and women representation. These recommendations were backed by reports submitted by a network called All India Network of NGOs and Individuals working with National Human Rights Institutions (AiNNI) from 2008 to 2024.

Specific problems within NHRC

The AiNNI made a joint submission with the Asia Network of NGOs and Individuals working with National Human Rights Institutions (ANNI) to the GANHRI on November 29, 2024. The submission quoted the concerns raised by the UN Human Rights Committee in July 2024 citing a lack of gender balance and representation of religious and ethnic minorities in the composition of the NHRC, opaque and exclusive appointment processes, lack of meaningful engagement with civil society, and involvement of police officers in the NHRC’s investigations of human rights violations, affecting the independence of the Commission.

In addition, the SCA in 2017, 2023 and 2024 particularly emphasised, “there may be a real or perceived conflict of interest in having police officers engaged in the investigation of human rights violations, particularly those committed by the police.” Although the PHRA empowers the government to appoint police officers for the efficient performance of the NHRC, there have been no significant steps taken until now. This has materially affected justice for victims of custodial deaths, which is conspicuous from the latest NHRC data as of September 2024. The numbers revealed that out of the 14 cases in which compensation was granted, none relates to death in police custody, whereas a total of 2,575 cases were pending under the category of police encounters and custodial deaths.

When the SCA repeatedly insisted on pluralism and accountability in the appointment of members and the Chairperson, including an amendment in the PHRA, the government amended the PHRA in 2019 to include a Supreme Court judge as the Chairperson. This move did nothing to increase pluralism in the Commission. On the other hand, the PHRA empowers the government to appoint civil servants with the rank of Secretary to the government for the role of Secretary General of the NHRC.

An analysis by AiNNI reveals the appointment of former officials or MPs associated with the ruling party in other commissions including the commission for minorities, children, etc in addition to the long-standing vacancies. The NHRC even appointed an IPS officer who was accused of corruption in 2018 as a special monitor to oversee counter-terrorism and communal riots. All this seriously undermines the autonomy and independence of the Commission.

Apart from independence and pluralism, the Commission has also lagged behind in its effective functioning and interventions. The Commission failed to intervene in the escalating crackdown on journalists and human rights defenders, hate speeches by right-wing extremists and bulldozing of Muslim homes. The NHRC utterly failed in its obligation to intervene in individual issues like the arbitrary detention of Umar Khalid, Gulfisha Fathima, Khurram Parvez, and the death of Prof GN Saibaba. The NHRC has also not been able to stop the violence in Manipur, let alone ensure the proper functioning of other related rights commissions.

The very process of the appointment of the new Chairperson was frowned upon by two members of the committee and opposition leaders Rahul Gandhi and Mallikarjun Kharge. They had suggested the names of former Supreme Court judges Justice RF Nariman and Justice KM Joseph for the post of Chairperson and former High Court judges Justice S Muralidhar and Justice Akil Kureshi for the post of members, citing their origin from minority communities and their track record in upholding human rights. This suggestion was totally ignored in the appointment process.

Light at the end of the tunnel?

At a time when rampant violations of human rights are taking place in the country, the new Chairperson needs to take the initiative to put some order in this institution of utmost importance. The problem of vacancies has been almost solved now, but aspects like pluralism, inclusivity and independence have to be revisited. Since the new Chairperson took over, the Commission has started to be vocal about major human rights issues in the country. On January 6, the NHRC held an open house discussion on various human rights issues, particularly tackling the menace of manual scavenging and several suggestions to improve the functioning of NHRC, including an amendment to the 1993 law. In a recent interview with the Times Now, Justice Ramasubramanian said that his top priority is to restore the ‘A’ status of the NHRC, and that his second is to restructure and strengthen the Commission.

To restore the ‘A’ status means to completely bring back order and discipline in the Commission in accordance with the Paris Principles. This means ensuring independence, pluralism and transparency in its appointment and effective functioning. The irony is that Justice Ramasubramanian’s own appointment is against the principles of the SCA recommendations, as two main members have shown their opposition publicly.

With the SCA review of the NHRC’s status coming up on March 12, it is very important for the Commission to roll up it sleeves. Losing accreditation of ‘A’ status means losing the opportunity to participate in the UN Human Rights Council and a few other UNGA bodies. This could be a major setback for India at the global level. Nonetheless, there are truly high hopes that this new Chairperson shall muster all his might, intellect and passion for human rights to bring back life to this once-adrift vessel that is entrusted with the duty to protect the lives of the most vulnerable sections of this nation.

Henri Tiphagne is a lawyer and the National Working Secretary of AiNNI. Edgar Kaiser is a legal researcher at AiNNI.